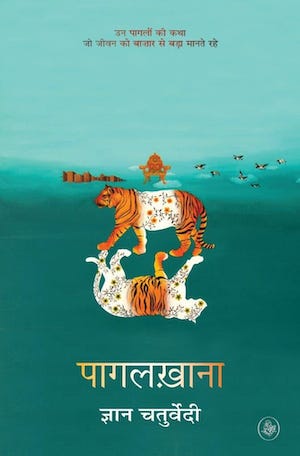

There’s a rhythm to all things, a heartbeat as it were, and if you are at all a regular reader of our feuilleton, you know we always open with the tooting of our trumpets. First, we’re pleased to announce the publication of Punarvasu Joshi’s The Madhouse (Niyogi Books), an English translation of Gyan Chaturvedi’s fifth novel Pagalkhana. Chaturvedi is not a fan of the marketplace; at least, the marketplace in its totalitarian incarnation. His novel’s cover is interestingly ominous. It features the same grinning scoundrel who took that nice English lady for a ride and returned with her inside.

Punarvasu Joshi is a TBLM author; in Issue 55, we’d published his English translation of a Hindi short story by his late father, Prabhu Joshi (“Nothingness”, August 2023). We don’t want to claim there’s cause and effect here, but we wouldn’t mind if you do.

The other piece of good news is that another one of our contributors, Maithreyi Karnoor, has just been awarded the Kuvempu Bhasha Bharati 2024 prize for her (English) translation of Vasudendra’s (Kannada) novel, Tejo Tungabhadra. Three cheers and a double scoop of jackfruit ice-cream for all.

In this marketing-driven age, the trumpet tooters may seem to have an overwhelming advantage. It is worth reminding ourselves that without silence, we cannot hear ourselves. In 1951, the composer John Cage spent some time in the anechoic chamber at Harvard University. A considerable mythology has accreted around this experience and how it led to the creation of his most iconic composition 4’33”. In a conversation with David Tudor, Cage recalled the oft-recalled experience:

It was after I got to Boston that I went into the anechoic chamber at Harvard University. Anybody who knows me knows this story. I am constantly telling it. Anyway, in that silent room, I heard two sounds, one high and one low. Afterward I asked the engineer in charge why, if the room was so silent, I had heard two sounds. He said, “Describe them.” I did. He said, “The high one was your nervous system in operation. The low one was your blood in circulation.”

Today’s colophon by Tashan Mehta is about that beat in the blood. It is when a body of impulses we call our work becomes embodied. It is about experiencing the feeling that Wordsworth refers to in the poem we now call Tintern Abbey:

These beauteous forms,

Through a long absence, have not been to me

As is a landscape to a blind man’s eye:

But oft, in lonely rooms, and ‘mid the din

Of towns and cities, I have owed to them,

In hours of weariness, sensations sweet,

Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart…

Take it from here, Tashan.

Colophon: For That Which Lives Outside Of Understanding

TASHAN MEHTA

In 2017, my first novel was published. I was wholly unprepared for what publication does to you: for the desire to be perceived and simultaneously hide; to oscillate between loving your work of art and despairing of it; to try and separate yourself from the work and fail.

But one of the most precious things that came from that time was that I discarded the concept of “good”.

Like anyone who sets out to create a work of art, I had set out to write something “good.” Yet if you had asked me what “good” was, I couldn’t define it for you. At the time, this didn’t worry me. Surely it was obvious? Good works of art have been celebrated throughout the ages: they sounded a certain way, unfolded a certain way, and cared about certain things. Nevermind that “good” works of art were also vastly different from each other. Or that what I’d read as the canon seemed distant from my experience or my interests (I never could find it in myself to care about Wordsworth and his long walks). But these were tiny hiccups, simple signs that my taste was lacking. Over time, it would develop. “Good” wasn’t a quality. It was a place, and you could reach it by traveling well-worn paths. All you needed was some skill and a map.

Yet, as it was now clear, “good” had not worked for me or my book. The place where I ended up hadn’t done my novel any favors. It had, to my imagination, crippled it. But if I was to sit down and write another one––a horrifying, painful proposition at the time––I needed the concept of “good”. Otherwise, what would I be aiming for?

Fuck it, I thought. Forget the place, the map, the right words. Turn into yourself. Aim for what’s alive.

This was my dramatic way of telling myself to listen to my instincts. What did I love in literature? What excited me, and why? If I had to make a canon, what would it look like? And once I had that personal canon, what could it teach me about the literature I cared about?

All of this took place nearly a decade ago, so it’s hard to drum up the urgency and delight I felt at finally giving myself freedom. (It was a wonderful time, though; if you’re still struggling to give yourself permission to do whatever the hell you want, let this be a catalyst.) What survives of that time is the word “alive”. Over the years, that word has moved beyond my personal interests and taste to become a theory of working.

#

It's difficult to give language to that which is nebulous––this quiet, blurry thing in the corner of your eye. You’re afraid if you look at it too closely, it will turn to smoke. The concept of aliveness is like that for me, and yet it has guided me, deftly, towards producing a work of art I am genuinely proud of. So here is my clumsy attempt at capturing it.

To make something alive is to make a work that exists outside of understanding. It does not only appeal to the mind, to the cold and the rational, but to the impulses we don’t understand ourselves. A truly alive piece of art does both: tickles the mind and hooks the heart. (Even as I type this, those binaries feel ridiculous; mind, body and heart are more entwined than we allow, but what other language do I have to describe this?) Perhaps a truer expression is to say that an alive piece of art will operate beyond the qualities you give it. It will stand on its own two feet and converse with the reader. It will move and breathe––and it will be wholly beyond you, its writer.

Think of it as a soul: a living, quivering thing that must be transported into the body of a book (by you, the writer) so that the reader may encounter it. What conversations the reader and the book have is not up to you; you are not in control of what the book does once it leaves your hands. All you can do is put that soul into the page––build the page such that the soul can live in it––so that when a reader opens it, they are conversing with a live entity.

Translators understand this better than anyone else. When I worked as a developmental editor for translations, I watched them perform necromancy––lifting the soul from a piece of text to place it into another language. Sometimes, that meant changing words, paragraphs, flow. Whatever it took to make the new text pliable for the spirit that was coming, to preserve the essence of what they were translating.

To think of work as “alive” changed my practice.

It meant that every time I wrote what I thought was “good”––and it was good by the standards of craft––I had to ask myself if it was alive. Did it stand up and add to the conversation? Did it help my book become a fully functioning entity? If the answer was no, I threw it out.

Every time I mapped out a safe and clean structure for a book, I asked myself if it was alive. Did I choose this shape because others had chosen it before? Or did I choose it because it brought the book closer to standing on its own two feet? If the answer was the first, I went back to the drawing board.

I did this repeatedly for my second novel. When I started the book, it was a simple novella about two people in a tower that vaguely resembled the tower of babel. Then I picked out a small character, a little bit of backstory, and pushed into it––until it became clear this backstory was the story. So, I mapped out this story on traditional fantasy lines: different kingdoms, warring priorities, clashing cultures. I filled multiple Google docs on worldbuilding.

Then I sat back and asked myself if it was alive. The answer was no.

It’s terrifying to look at two to three years’ worth of work and realize it doesn’t meet a standard you’ve set for yourself. At that point, you’re tempted to throw away the standard. After all, what does it mean to “make something alive”? I can barely describe it to you now, so I certainly couldn’t describe it to myself then. Why not just trunk it, like I trunked the idea of good?

I don’t know why I didn’t. Instead, I discovered that infusing a work with life was often about how you looked at it. I learned this by accident. I was watching In This Corner of The World, a heartbreaking animated film about Japan in World War I. There was a scene where a character was standing at the edge of a cliff, watching these ships, the wind blowing her hair and skirt. But the angle it was sketched from was not the front; it was from the left-hand lower corner of the frame, as if we were below her, looking up. The effect of that… I don’t know, I cannot describe it. By simply positioning me somewhere other than I expected to be, by shaping how I looked and experienced the scene, the animators undid me.

Later, I would read Italo Calvino’s Six Memos for the Next Millennium where he would talk about lightness and quickness in prose. The world was turning to stone, he wrote, “a slow petrification”. His goal was to combat it. “My method has entailed, more often than not, the subtraction of weight. I have tried to remove weight from human figures, from celestial bodies, from cities. Above all, I have tried to remove weight from the structure of the story and from language.”

Both experiences mapped onto each other. How you wrote about something changed what you wrote about. The same story or scene, the same people, transformed when approached with a different voice, or perspective, or style. Voice, perspective, style––these are all heavy words. What I am reaching for is more delicate than this. I see it as a wooden globe, held out in someone’s hand: once whole, now hollowed and intricately carved. Same globe, and yet a different globe. Transformation, within the boundaries of the old.

The story of my novel, I realized, was the right one. I knew its essential pulse. What I needed was to bring the lifeforce to the surface––and to do that, I had to see it correctly.

And to do that, I had to change.

#

When I talk about my second novel, I worry that people believe I am advocating for cruel perseverance. Endless drafting. The brutal discarding of old work that doesn’t serve a purpose. The consistent pushing of one’s talents until one despairs (until, miraculously, you despair no longer). I suppose I do believe in rigor in the art, in learning the alchemy of the craft. But what I am really saying is: if you chase aliveness in the art, then you need to be pliable to the alchemy of the self.

To look at a story in the right way, to find that angle that lifts it into the realm of the living, you must become the right person. I don’t know how else to describe this except alchemy. I imagine neurons rewiring, associations drifting and then locking into new positions, emotions cresting and subsiding on foreign logic dictated by the needs of the novel. In short, alchemy. A transformation of the self that makes you the right person to write the story.

This moves beyond voice, perspective, style, or structure––any of those key terms we use to pluck apart an existing work. This cannot live in the conscious part of your brain, the one that chooses a style, or plans a structure, or writes pages and pages in the hope of practicing a certain voice. This is a way of seeing that must become second nature, effortless, produced without thought. It means that when you traverse the realm of the story––those tiny facts you do know, the pieces you are sure slot together somehow––you are able to move among them lightly, able to pick, pluck and carve with flow and ease, because you trust yourself, the person you have become, to see it correctly.

“Correctly,” of course, changes with every book. And thus, so must you.

Here’s a simple way of thinking about it. The book you’re writing, the story, the people, everything, exists. It’s out there somewhere, shrouded from you, and you can see it only in pieces. To join those pieces correctly, to make them more than the sum of their parts, you must become the right interpreter of the information you’re receiving. You ask the right questions. You handle knowledge with tenderness or fierceness or horror––whatever the book demands. You learn to open yourself up such that the book moves through you, so that when you reach for language, you order those words on the page in the most powerful sequence. Because that’s all that writing is, really: the right words in the right order.

I’m aware this sounds like witchcraft. It is, of sorts. Since finishing my second novel, I’ve picked up sketching and it has only convinced me of this transformation. I am no artist. But even with my humble ambitions for this form, I can sense a change within myself, a shift in how I see. I’ve spent my life admiring pen and ink sketches and wondering how one does them. Now I look out of a window and think, Oh, this is how I would frame it, this is the shading style I’d choose, and here are the brushstrokes that would bring out the essence of the scene. The world transforms: a shift from color, to black and white lines, then back to color. I adore it. It feels like a gift, mine to forever keep.

This is what chasing aliveness gives you. Multiple ways of seeing, all housed in your singular body. Gifts that cannot be taken away, yours forever to keep.

——

TASHAN MEHTA is the author of Mad Sisters of Esi, which won the 2024 Auther Award for Best Novel and the Subjective Chaos Kind of Award for Best Fantasy, and The Liar’s Weave, which was shortlisted for the Prabha Khaitan Woman’s Voice Award. Her short stories have featured in Magical Women, the Gollancz Book of South Asian Science Fiction Volume 2 and PodCastle. She was fellow at the 2015 and 2021 Sangam House International Writers’ Residency, India, and writer-in-residence at Anglia Ruskin University, UK. You can find out more about her at tashanmehta.com.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Banner image: William Havell. Tintern Abbey in a bend of the Wye, (1804); the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Image, courtesy Wiki Images.

We hope you enjoyed reading this issue of Crow & Colophon. Subscribe for free to receive updates about The Bombay Literary Magazine and notes of a literary persuasion.

Pause. Linger. Observe. - A Writer's Life. Reminded me of Woolf who took nine years to write her first novel.