Impossible Dreams

When artificial people dream in their syntactical sleep

Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again. It seemed to me I stood by the iron gate leading to the drive, and for a while I could not enter, for the way was barred to me. There was a padlock and a chain upon the gate. I called in my dream to the lodge-keeper, and had no answer, and peering closer through the rusted spokes of the gate I saw that the lodge was uninhabited.

Who is this ‘I’? In the opening paragraph of Rebecca, Daphne Du Maurier’s classic novel, the first ‘I’ refers to the eponymous heroine. But the ‘I’ standing at the gates of Manderley exists only in Rebecca’s dream. For that matter, ‘Rebecca’ also only exists only as a construct of our minds, entangled with the author’s words. Exactly who is standing at the gates of Manderley?

In this post’s colophon, we offer David Mitchell’s thoughts on the deployment of dreams in literature. It is a long-ish essay, which is as it should be, since prose writers, unlike poets, have the decency not to leave it to the reader to clean up after them. On dreams then, about 4,600 words.

Colophon: What Use Are Dreams In Fiction

DAVID MITCHELL

Rather than attempt a taxonomy of how dreams have been portrayed and deployed by writers down the ages, a task which many people in this room could perform with more erudition than me, I would like to re-hang the title of this talk [1] and look at it this way: in a dim recess of the writer’s shed there is a tool called ‘dreams’. What are the hazards of using this tool, and what results can be achieved with it?

Hazards, then, first. One reason a novelist might advise an apprentice not to go near this tool called dreams, is simply that fiction itself is already one remove from reality. We could call this remove, ‘ontological distance’. In common with dreams, fiction is a theatre within the mind where the audience of one— ‘You, Dear Reader’—watches a sequence of made-up people leading lives that, outside the theatre of the mind, do not exist. If the ‘acting’—that is, the writing— is skilled, we will succumb to the illusion that the set and the cast are real places and real people, up to a point. But to write a dream and insert it into the fiction runs the risk of weakening the illusion by doubling it. In short, the suspension of disbelief will only go one layer of reality down. Two layers or more, and it pops. As with ontological distance, incidentally, so for emotional. We can care what happens to a character one level of reality down: going down two, to a dream within a story, is another tough act to pull off. ‘Oh no you don’t’, I tell Charles Maturin, author of Melmoth the Wanderer, ‘you’ve already said that this is a vision inside a recollection inside a manuscript, etc., and I’m afraid I just don’t believe these people are real any more. And if they aren’t real, why should I care about them?’

A closely related reason for not using dreams in fiction is, perhaps counter intuitively, dullness. The chief oneiric art movement, Surrealism, may make a strong first impression on the eye and dovetail well with contemporary theories of consciousness—witness the many books that have This Is Not A Pipe on their covers—but by the fourth or fifth Magritte or Dalí in the museum, I’m afraid my twenty-first-century eyes glaze over. I don’t wish to pass off a personal distaste as proof, but other peoples’ dreams, unless they feature yourself or something truly extraordinary, require the same yawn-suppression and polite noises as other peoples’ holiday snapshots. Dreams have a lexical reputation for being more exciting than ‘Reality’, but you have to be crazily in love with someone to take more than a minute or two of hearing about theirs. For every Lynchian epic of a glowing, glorious dream, there are 50 trashy slap-dash B-movies. Dreams cannot be anything other than intensely, exclusively personal. It is hard to think of another basic human function that not only can be experienced alone, but that can only be experienced alone. Dying? Sleep, maybe, but then sleep is a prerequisite for dreaming. Reading might be the closest not-quite-basic human function. We can read in company, of course, but your Narnia, your Wuthering Heights, your Hogwarts, will not be the same as mine. Unless we both watch the films, but that is a whole different shebang.

From what I’ve said so far about the problems arising from using dreams in fiction, symptoms of the Faerie Queen Syndrome are becoming detectable. Spenser’s masterpiece has a deserved seat in Elizabethan literature courses the world over, but when I read it for a course at this very university, I remember that my reaction—galloped to page 10, slowed by page 30, begging for mercy by page 50—was pretty typical. Admittedly this might be saying more about the undergraduates of 1987 than about Spenser, but I’d still defend the principle that staying interested in a world whose inhabitants wear their unreality so on their sleeves is a tall order. ‘You’re missing the point’, an objector may interrupt. ‘The Faerie Queen was an encrypted, extended metaphor. The Vision of Piers Plowman was an expression of Christian mysticism. The Gaelic aisling was a depository of folklore. It’s not the fault of these dream-works if you find them dull.’ Such an objection would probably shut me up, though I would say that Swift knew what he was doing when he called it Gulliver’s Travels and not Gulliver’s Dreams. I would also add that dreams are very difficult for the mind to recreate convincingly in written prose. You can put in the ingredients we associate with dreams—kookiness, illogical juxtaposition, evanescence, abruptness of scene change—but the key ingredient, which I can only call ‘dreamlikeness’, is damned nigh impossible to capture. I know it when it’s there, but if I try to define ‘dreamlikeness’, it slips away like dreams themselves in the first moments after waking. Fine writing is known to the conscious mind by its clarity and precision. Dreamlikeness is known to the conscious mind chiefly by its pell-mell exodus.

My hypothetical novelist, still warning his or her apprentice about the dangers of incorporating dreams into fiction, now moves onto plot. Plots in dreams are farcical, fragmentary, discontinuous affairs. Dreams have well and truly ‘lost the plot’, as we say these days. Scenes are not coherently ordered A, B, C. Rather, they kick off at K, stall at S, then veer to V. Useful novelistic staples like exposition are nonexistent. A week or so ago, I dreamt I was at my friend Bernie’s house near Brisbane, with no explanation of how I came to be here or where Bernie was or why his happily neglected garden had been replaced by sheets of light. Nor did I ever find out how I got from Brisbane to my local supermarket in West Cork, immediately afterwards. Or why the songwriter Leonard Cohen was hiding in the next aisle, where the kitchen towels and buy-two-get-one-free packs of depressingly cheap clothing are kept. ‘You tell me, then’, my hypothetical novelist might say, ‘What use could this rubbish possibly be put to in a decent piece of fiction?’ My apprentice would nervously ask why fiction must follow the dictates of realism so slavishly? The Guyana Quartet by Wilson Harris is plotted with the illogic of dreams. Dead people come back to life without even a reference to their own deaths. ‘Maybe so’, replies my novelist, smugly, ‘but nobody’s heard of it.’ The apprentice tries his luck with Gogol and Kafka. But the novelist argues that stories such as Gogol’s nose and Kafka’s beetle work because the minority oneiric elements are always beholden to majority diurnal logic. The stories may think one or two impossible things before breakfast, but subsequently they follow a causal, realist line of logic to their grim conclusions. We sympathize with the protagonists because they have to try to handle their ghastly derailments with the same inadequate equipment which we too would have to rely on. There are no dream-teleport devices to whisk them to safety. Joseph K. is not woken up by his Mum. One dreamlike event does not a dream narrative make. ‘What about magical realism?’ asks the apprentice. The novelist cuts himself a slice of cake, eats it and repeats an opinion he heard at a literary conference. Magical realism can work for Marquez and the South Americans where it is an instrument of political subversion, or to evade censorship, but name one truly great novel outside that context where the magical realism isn’t simply a generator of fairy-light imagery?

‘Okay’, says the apprentice. ‘What about Alice in Wonderland? That’s a dreamlike narrative that’s gone the distance, surely?’

‘Glad you asked me that’, says the novelist, looking at his watch. ‘I’ll, uh, come to that later.’

The long-suffering apprentice has two cards left to play, though neither of them is very strong. One is character. If dreams can’t add anything to plot or structure, can’t they enhance character? Say you have a psychopath who doesn’t know he’s a psychopath. Couldn’t you drop hints to both the character and reader that he has the potential to kill by, say, having him dream about dismembering lambs and eating their entrails?

The problem here is that dreams, for believers of the faith, are so loaded with symbol that you (the reader) need hours with a highly trained (and highly paid) psychoanalyst to decode them; or else dreams are so clodhoppingly clear that the information ‘smuggled’ into the dream should already be obvious to the reader from the character’s waking life or mannerisms. Why load your narrative with the closet psycho’s grisly dreams, when you could give the same information by, say, having him harbour a knife-sharpening fetish instead?

The last card is this. One propensity and compulsion of a writer is to pan for gold in the river-bed of the quotidian and the vernacular. Conversations, articles, TV, that couple having a row on the Whitstable bus—and, the apprentice would say, why not dreams?

The problem here is quality. I’ve sometimes started waking and thought, ‘Gold! What a story that dream would make!’ only to be fully awake later on, and think, ‘What utter drivel. I must have still been half-asleep to have thought that was a useable idea.’ It is as common and easy to dream that fool’s gold is real gold as it is to dream that one’s skill in a foreign tongue is effortlessly fluent. No. Dreams are what flies out of the mind’s garbage chute and there is nothing more to say on the matter.

We’re at the half-way point. So far, I’ve argued for the rule of thumb that says dreams are of no practical use for writers of fiction. Writers of fiction can, by the way, usefully bind themselves up in rules about writing because the acts of escapology necessary to wriggle out of these rules are what originality is. Now I would like to argue the case that dreams are of use in fiction. Some of the arguments are shameless contradictions of the arguments against using them that came up in the first half. But I feel able to practise this fancy footwork because (a) dreams themselves are prone to shameless contradictions and (b) a volte-face is an easier trick to perform when one is here in word but not in body.

Several paragraphs ago I said that dreams rip holes in the fabric of fiction because of their ‘removedness’ from reality. To portray this ‘reality’ is a primary aim of fiction, so holes are not welcome. But what if a primary aim of a given piece of fiction is to examine this very ‘removedness’? To probe these very holes in the fabric? To study the theories and practices of ontology?

The adjective ‘Borgesian’ hasn’t yet joined ‘Kafkaesque’ or ‘Orwellian’ in my OED, but I’d bet it’s only a matter of time. The purblind librarian of Buenos Aires staked out much metaphysical turf and his name is still on the deeds. One of Borges’ most austere, arresting stories is ‘The Circular Ruins’, about a holy man who forsakes the waking world to dream a progeny into existence, organ by organ, hair by hair. The ‘dream-son’ (Borges, 1970: 76) is finally given life by the deity who was once worshipped in the eponymous ruins in which the father has taken up an ascetic’s existence. The deity’s earthly name, we are told, is Fire (1970: 75). Only Fire and the boy’s father will know that the boy was not conceived and born in the usual manner. Some time after the boy has left to make his own way in the world, a forest fire encircles the ruins and the father.

He walked into the shreds of flame. But they did not bite into his flesh, they caressed him and engulfed him without heat or combustion. With relief, with humiliation, with terror, he understood that he too was a mere appearance, dreamt by another. (1970: 77)

What a gorgeous exposition of solipsism is this dream-framed story of Borges’. If its dream elements are removed, the story would disappear into thin air.

Not so well known as Borges, even in a decade when Japanese fiction gets into Waterstones’ Top 30, is the early modernist and sometime student of Zen Buddhism, Natsume Sōseki. In his short story ‘The Third Night’, which begins, in fact, with the words ‘I dreamt’ (Sōseki, 1969: 317), the narrator describes a walk through a crepuscular landscape of rice fields and trees. He carries and converses with the blind child on his back, who may or may not be his own offspring. The narrator has only a foggy half-idea of what he is doing and where and why. A page later the child directs the narrator to the root of a cedar tree and tells him, ‘It was exactly one hundred years ago that you murdered me.’ The narrator tells us,

As soon as I heard these words, the realization burst upon me that I had killed a blind man, at the root of this cedar tree, on just so dark a night, in the fifth year of Bunka, one hundred years ago. And at that moment, when I knew that I had murdered, the child on my back became as heavy as a god of stone. (1969: 318)

This précis doesn’t do Sōseki’s story much justice: please take my word for it, it works. It evokes the atmosphere of dreams, and is painted with the blurredness of dreams, to illustrate the notion of karma. What ‘The Circular Ruins’ and ‘The Third Night’ have in common is that they use dreams to create a working model of a metaphysical conceit. In doing so, they metamorphose the question, ‘What Use Are Dreams in Fiction?’ into the statement, ‘Look At What Is Possible When A Gifted Writer Does Use Dreams in Fiction’. Doubtless in the course of this conference other such gems of short fiction—and they tend to be short because, at least when described from outside the sleeping mind, brevity is another quality of dreams—have been and will be unearthed and analysed.

More prosaically and less metaphysically, dreams have a home in the theatre of fiction simply because dreams too are a part of that same human condition that it is fiction’s vocation to probe and to mirror. Flesh-and-blood people dream. Why not have fictional characters do the same? Especially if the fictional dream can be harnessed to a practical dramatic purpose, such as facilitating a plot twist—as distinct from being the plot. I happen to remember the first dream I ever encountered in fiction, and being very impressed with this device at the time. It comes half-way through one of five or six books for children written by the British novelist Penelope Lively in the 1970s, The Whispering Knights, where three children unwittingly evoke an evil spirit, one of whose manifestations is Morgan le Fay. Martha, the most empathic of the three children, is prone to vivid dreams. Morgan le Fay uses these as a conduit through which to ‘magick’ Martha, and possess her will:

In the night Martha dreamed. She dreamed of a sea: it was a milky-green sea, flecked with foam and veined with colour, like liquid marble. It seemed to be calling her, with soft, enticing voices, and when she sank into it it was warm and enfolding like a bed, but somewhere far away, in another world, there was a thin voice screaming. She woke, slowly, and the enfolding warmth was her bed, and somewhere outside the window there was a strange noise ... (Lively, 1973: 86)

Stirring, spooky stuff, I thought as a 10-year-old, and I still do. You don’t have to believe that dreams can be a conduit for demonic possession to enjoy a story where this happens, any more than you have to believe that dreams possess prophetic qualities to appreciate the one where Joseph interprets the Pharaoh’s dream of years of plenty followed by years of famine. A dream can sometimes be simply a useful and pleasing plot device. Humans dream, many humans ascribe supernatural properties to dream, and the business of fiction is the human condition. Isn’t this enough?

Perhaps it is exactly this quality of dreams that fiction writers can best utilize: their universality. Humans are born, breathe, eat, drink, need shelter, reproduce, die and dream. Dreaming is near the genderless feet of the totem pole of Homo sapiens’ common denominators. Even with my feeble grasp of neurology, I feel confident in asserting that what those people who say, sometimes with a touch of pride, ‘I never dream’ mean is: ‘I don’t remember my dreams.’ (Bet they do sometimes, though.) Empathy with characters is what makes readers care about their fates and stay on board the book. Generating this empathy, this closeness, is a knack all writers need to acquire. Part of the knack is persuading your readers that your fictional creations are creatures with similar habits, vulnerabilities and strengths as your readers. Dreaming is as good a tool as any for achieving this end. Watching my wife mumble in her sleep as her eyeballs go crazy beneath their eyelids, or seeing my parents’ now defunct border-terrier’s hind legs bound as he dreams of chasing dusters across fields, or hearing my three-year old wake up in the night crying ‘No Daddy! It’s MY apple pie!’ generates, in my breast anyway, an almost painful intimacy. My son was born seven days ago, and there isn’t much I wouldn’t give to be able to watch his dreams via some not-yet-invented machine. My point is that although the hypothetical novelist in Part One of this lecture described other peoples’ dreams as dull, it was actually his own dullness he was describing. Intimacy and curiosity trail in the wake of other peoples’ dreams like the particles of a comet’s tail. These elements are fecund with fictional possibility.

It is a truism to say that the surest way to remember dreams with maximum clarity is to want to remember them. The period of clearest dream recall in my life was as a first-year undergraduate, when, having enrolled on a Psychoanalysis and Literature course, my classmates and I were asked to keep a dream diary. Going to bed every night knowing that this dream diary waited to be filled in the morning had the effect of pressing PLAY and RECORD as I fell asleep. I hope I recorded my dreams as truthfully as I could, but what interests me now is how, when recounting dreams to my wife or a friend the day after, I am unable to resist embellishing them, and assembling them into some kind of a crude narrative. When, for example, I emailed another friend about the Brisbane/West Cork supermarket dream I added the detail that I went off in search of Leonard Cohen to ask him what the hell his nutty song ‘Jazz Police’ off his recording I’m Your Man—a song my friend and I have discussed at length— meant. As well as explaining why I followed my vocation into creative writing rather than academia, this embellishment stiffened my gelatinous dream into a better story. By lunchtime of the day after a significant dream, these embellishments have themselves been embellished, and by evening I’m not always sure what part of the narrative was my original dream, and what parts I’ve added since. My point is that this process, of adding invented facts to dreamt ones, of editing and rewriting, of allowing the stronger dramatic elements to nudge out the weaker, bears a striking resemblance to writing fiction. So if I ever corner you in a bar and say, ‘You won’t believe what I dreamt last night’, you should take what I say with a pinch of salt. But, in a way, novelists, even more than cabinet ministers or estate agents, must lie for a living. When I indulge in fantasies about running a Creative Writing MA Course, then, it isn’t a dream diary that I ask my students to keep, but a Doctored Dream Diary.

Nuggets of gold that we pick up in dreams mostly turn out, on waking, to be fool’s gold, but occasionally fool’s gold can actually turn out to be real gold. When I lived in Hiroshima, early one morning in the rainy season, I saw a wooden box had been placed at the end of my futon. I crawled up to this box, undid its clasp and opened it up. Inside was a folded piece of paper. I unfolded the paper and read the words, ‘The Language of Mountains is Rain’. Next, I woke up. But the words stayed with me. They still strike me as beautiful, all the more so because I feel I had nothing to do with them. In the end, I used them as a chapter title in my second book. Paul McCartney, Beatles mythology claims, got the chord changes of his song ‘Yesterday’ as he woke from a dream. An even more famous example of dream-gold is Coleridge’s Kubla Khan dream. John Banville has his recreated Kepler see a certain, precise, golden number in a dream, which he forgets upon waking and is fated, or driven, to spend the rest of his life trying to calculate. Occasionally

Morpheus places a 24-carat nugget in your palm and all you can do is breathlessly thank him, and do your best not to drop it before you get it safely into your notebook (sometimes I think the act of waking is as fascinating as the act of sleeping).

A further quality of dreams that is not so much useful as crucial for a writer of fiction is clichélessness. Fiction—poetry even more so—needs clichélessness like baby tomato plants need Tomato-Mate. Dreams are rich with clichélessness, with never-encountered combinations of the ever-countered. We’ve all seen cats, sometimes fat and even semi-stripey ones, and we all know what a smile is, but the Cheshire Cat and its slowly fading grin is something really special. A caterpillar on a mushroom, yes; but a late Victorian caterpillar on a mushroom smoking a bong beyond the wildest dreams of Syd Barrett? Wow. Unexpected size-changes, babies morphing into sheep, exitlessness, a lack of justice, antagonists’ extreme unpredictability, iron-cast laws that keep changing, running hard but going nowhere, tenaciously inaccessible destinations: Carrol’s stitchwork is perfect, invisible. He avoids the quicksand of his carte blanche by disciplining his dream-worlds with logic and mathematics, yet these rules are glimpsed by Alice (and most non-academic readers) only dimly. It is not quite true to say that anything goes in dreams, or in fictional representations of dreams – the wrongness has to be precisely right. At a push, you could use flamingos for croquet mallets. Sort of. Flamingos are righter—by which I mean more dreamlike—than garden rakes, or sleepy crocodiles. Tweedledum and Tweedledee’s monstrous crow, similarly, works better than a monstrous eagle or bat or flying bicycle because, I would argue, the crow is somehow more likely to interrupt an argument about a nice new rattle. It is this perfection of dream-pitch that, I believe, makes Alice immune to gaps and barriers of age, generation, culture and language. If only one book outlives our suicide-bound species for those life-forms that the indestructible slugs in my garden will evolve into to dig up and put in their Natural History Museum, let it be Alice Through the Looking Glass. It is a text built from human dreams, and so houses what humans are.

Fear, as professional writers since the Beowulf bard to Stephen King have known, animates fiction as effectively as a certain rune animates golems. People pay good money to be scared in a controlled environment. And where better to look for what petrifies the human mind than those horror movies we ourselves produce, direct and star in? Nightmares. The Mary Whitehouse of the unconscious mind—speaking for myself, anyway—nods long and often. Nightmares of casual violence, of gratuitous gore, ingenious ones, corny nightmares with vampires and werewolves….I like to think I’ve dreamt a good sample. I seem to specialize in eschatological nightmares, where I and a dwindling band of doomed survivors wander war-torn landscapes, or towns populated by bands of the ‘turned’: the demon—or alien-possessed, or victims of some zombifying disease, or, during the Cold War, the irradiated living-dead. I can’t gauge to what degree these nightmares came from too much J. G. Ballard or John Wyndham in my early diet, any more than I can measure what percentage of 28 Days Later, The Ring, half of Poe’s output, The Shining or Mulholland Drive—and any one of us could probably go on and on—trickled into their creators’ imaginations through the filter of nightmare. But nightmare is undeniably a rich, rich vein.

I could probably cut this paragraph, but the most nightmarish sensation I know is the doubt than I am me and that the solid walls of reality are gaseous illusion. The worst that golems and monsters can do to you, after all, is tear you limb from limb and devour your vital organs, which is unpleasant but probably brief. Losing your mind, however—without even knowing it—is a darker proposition. What dreams have in common with Alzheimer’s is that the here and now we believe we are in is not the here and now that everyone else shares. When the dream state overruns the border of waking, medically, we call it insanity.

I’ll stop now, because it’s time to wake up. What use are dreams in fiction? Quite a lot, if used judiciously, if it suits you and suits what and how you’re writing. This, and only this, is my unsnappy conclusion, but its unsnappiness isn’t all my fault. The seated journey of writing fiction has no highway code, no road atlas and no Lonely Planet. The only guides are your instinct, your experiences and those observations you pick up from fellow travellers.

NOTES:

[1] The paper, originally a lecture delivered on 15 October 2005, at the ‘Dream Writing’ conference at the University of Kent. David Mitchell was unable to attend and give the lecture in person, which he had intended to do, because of the arrival of his son Noah that month. The lecture was instead read by Professor Rod Edmond. [TBLM editors: ]

References:

Borges, J. L. (1970) ‘The Circular Ruins’, trans. James E. Irby, in J. L. Borges,

Labyrinths: Selected and Other Writings, pp. 72–7. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Lively, P. (1973) The Whispering Knights. London: Pan. Mitchell, D. (1999) Ghostwritten. London: Sceptre.

Mitchell, D. (2001) number9dream. London: Sceptre. Mitchell, D. (2004) Cloud Atlas. London: Sceptre.

Mitchell, D. (2006) Black Swan Green. London: Sceptre Publishers.

Sōseki, N. (1969) ’The Third Night’ in ‘ Ten Nights of Dream’ (1908), trans. Itō Akiko and Graeme Wilson, Japan Quarterly, 16(3): 317–18.

Source: First published in Journal of European Studies 38(4). pp. 431–441. 2008. © SAGE Publications. http://jes.sagepub.com. [TBLM eds: we have excised a couple of sentences from the start & finish of the essay for clarity.]

——

DAVID MITCHELL (1969—) is the author of many fine novels including number9dream (2001), Cloud Atlas (2004), and most recently Utopia Avenue (2020). His novel From Me Flows What You Call Time (2016) has time-capsuled and will be available to the reading public, if there is one, in 2116 AD.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

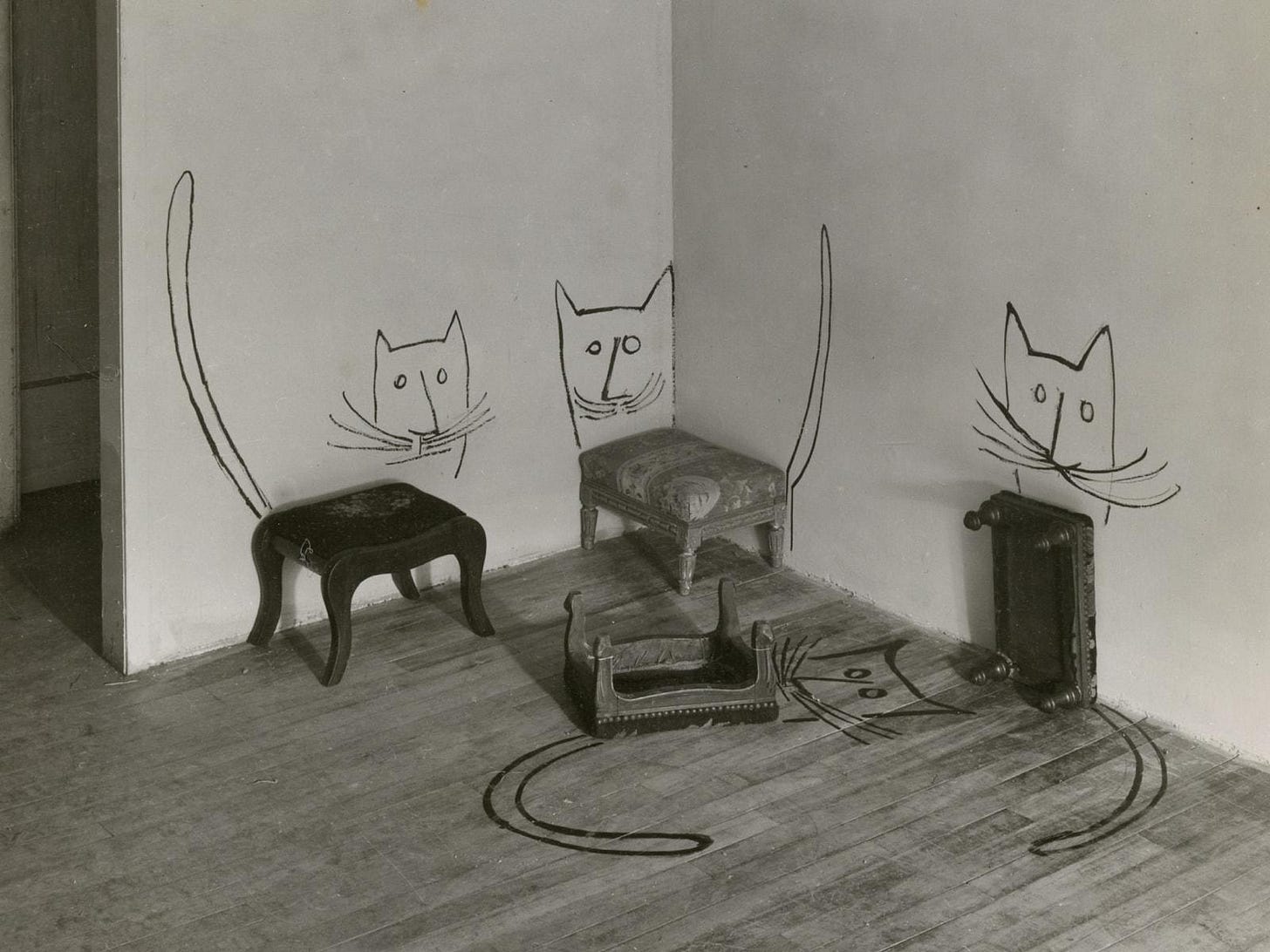

Banner image: Saul Steinberg. Untitled (Four Cats), 1950.

It is a fact—one that any painter will unrepentantly acknowledge— that there are no great paintings around the theme of dreams. None. Zero. Non-existent heart of a null set. We consider ourselves excused.

We hope you enjoyed reading this issue of Crow & Colophon. Subscribe for free to receive updates about The Bombay Literary Magazine and notes of a literary persuasion. For information about how to send your work to The Bombay Literary Magazine, please visit our submit page.