In C. S. Lewis’ The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe, there’s a scene where Mr. Beaver takes the just-arrived kids to see his dam.

They were standing on the edge of a steep, narrow valley at the bottom of which ran — at least it would have been running if it hadn’t been frozen — a fairly large river. Just below them a dam had been built across this river, and when they saw it everyone suddenly remembered that of course beavers are always making dams and felt quite sure that Mr Beaver had made this one. They also noticed that he now had a sort of modest expression on his, face — the sort of look people have when you are visiting a garden they’ve made or reading a story they’ve written. So it was only common politeness when Susan said, “What a lovely dam!” And Mr Beaver didn’t say “Hush” this time but “Merely a trifle! Merely a trifle! And it isn’t really finished!”

The August Issue of The Bombay Literary Magazine (No. 58) is now available for your perusal. Merely a trifle! Merely a trifle! And it isn’t really finished. 😊

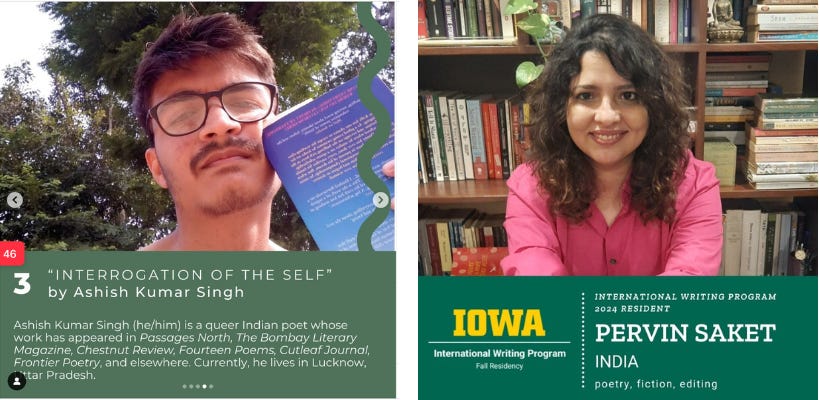

There’s more good news: Ashish Kumar Singh, Poetry Reader at TBLM, is one of the four winners of Singapore Unbound’s 10th Poetry Contest. Before Ashish joined TBLM, we’d published his poems in Issue 52. Also, Pervin Saket, TBLM’s Poetry Editor, will be attending the Fall Residency at the International Writing Program 2024 at the University of Iowa.

Onwards to the colophon. August 15 is India’s independence day. Independence and freedom are taken to be near-synonymous, but just as there’s a difference between “ownership” and “control”, freedom may come well before independence. One needn’t imply the other. (Or perhaps it’s the other way around. We don’t care. We have a new issue out.)

In his essay, Tanuj Solanki looks at the year he has had, since he quit his salaried job. The shift from salaryman to scribe is one that frequently comes up among writers, and Tanuj’s account may serve either as evocation or encouragement regarding your encounter with the Viliya.

Colophon: Crossing the Viliya

TANUJ SOLANKI

On 30 September 2023, I quit my career in the insurance industry. This was done not so much to become a full-time writer (I’d no conception of what that entailed) but to commit a definitive gesture in the service of an idea that had weighed on me for more than a decade: that a life with more time for reading and writing would be a better life for me. In six weeks from now, that action will reach its first anniversary. A year-end review—to use a concept from my erstwhile career—seems necessary. If I talk cursorily, upar upar se, I might say that it has been a period of ups and downs, as expected. If I talk more candidly, I might declare that the last ten and a half months have been more deflating than uplifting. If I talk comprehendingly, however, post an effort to probe the matter and reach somewhere near its complex heart, I might say that starting with the original departure from a career, the period has been a series of departures and arrivals, each one illuminating a malaise and its resolution. This sequence of illumination, the lighting of bulbs in the mulch of the self and its anxious presents, is nowhere near complete. It’s not easy to just read and write.

Things went well in the beginning, for about three weeks or so. I made rapid progress in my novel, averaging about 1,000 words a day as per a ledger I maintained at the time. I posted images of this ledger regularly on Instagram, revelling in the admiration of some of those who followed me and imagining a fair bit of envy in a large subset of those who offered no reaction. Sometimes, I even posted, in the way of providing a sneak peak, a paragraph or segment right after writing it. Writers don’t usually do this—that is, share parts of a work which is still being written—but I felt radically showy (or showily radical?) in those days. Convinced of my writing momentum, I even declared to my publisher that I would hand in the novel by the end of the year. I was writing loudly, publicly. Some part of this exhibitionism owed its existence to the brio of a new freedom, of having 9 to 5 unlocked. But what really fueled my posturing was my relationship with social media, which had altered significantly with my last novel, Manjhi’s Mayhem. I had promoted that novel very actively on Instagram and Twitter since its publication in November 2022. I had even taught myself some basic tricks on Canva, and had made professional-looking reels and carousel posts. The volume of response I’d received had been significant, higher than anything I had ever known. By October 2023, however, I was accustomed to that volume of engagement. In fact, I was somewhere between ‘accustomed’ and ‘addicted’. And the minor inconvenience of there being no novel to gloat about wasn’t going to come in the way: I would just borrow gloating capital from the future. It helped that my WIP novel was a sequel to Manjhi’s Mayhem and offered a degree of continuity on social media, though today—eight and a half months into the next year; the sequel still not complete—I wonder if the cart was always in front of the horse: was I writing a sequel because I wanted continuity on social media?

A late-October vacation with Nikita (my wife) put on hiatus the writing and the Instagram posting about the writing. There was some good old reflection. Upon realising that the pace at which I was progressing with the novel often led to bad writing, and that the ledger images of today were only a screen for the enormous editorial effort that would be necessary tomorrow, I shed the delusion that I would be able to finish the novel inside 2023. Nikita and I began deliberating the economising changes we needed to make, given that my contribution to our expenses and savings was going to be considerably lower. I also tried to develop some concept of what being a full-time writer meant for me, along with its necessary, and necessarily ugly, ecosystems of productivity and pay. These lines of thought brought me back, however, to a language of fuss and frenzy. I remembered what a professor of mine (also an industrialist, and one of the sharpest minds I know) had told me back in June 2023: that the only way to make it as a writer in India was ‘to become famous’. He did not mean Shahrukh Khan-level famous; he meant a level of famous that granted a sizable, unflinching readership—which is to say that your name was known not just in the writing or publishing community but in wider and numerous pools of readerships. I had known the fame requirement intuitively, of course, intuitively and from the deplorable economics of the publishing industry. A truckload of social capital was a precondition, not a curse or reward, for those who hoped to persist with a reading-writing life without a fat inheritance or a decade or more of dollar earnings. The only accessible way I had of taking a shot at building up clout was social media. To puff up my chest daily and to show myself as ‘a writer’. To announce my arrival to literature every day. To constantly memorialise—in a phenomenally ephemeral medium—my awesomeness. Social media was thus debt and equity both. I acknowledged it was harming my writing; I acknowledged it was necessary for my writing.

We returned from that vacation with altered immediacies and leniencies: (1) we needed to immediately make some economising adjustments; (2) I could be somewhat lenient in the writing of my novel, for it was going to take long anyway; and (3) there could be no leniency in social-media effort; in fact, I needed to think of ways to do it better, always to do it better. These immediacies and leniencies had the semblance of a plan, but they proved to be a recipe for anxiety. They rightly shifted my only possible achievement (the finishing of the novel) to a hazy point far in the future and rightly made me think of other ways to keep building social capital. But the perceived strains of these two rights, and the stress of contradiction in them, produced a load of disaffection in me.

Nothing notable happened in my reading-writing life for weeks after the vacation, nothing notable apart from the surfacing of some renegade impulses: I wanted to vanish from Instagram and Twitter; I wanted to drastically alter my reading choices and routines; I wanted to take up abstruse writing projects of no particular relevance to anybody. It was plain that, severed from the naive alacrity of those early days of freedom, I was now in the charged proximity of my real desire: to liberate my writing persona from its cultivated hubbub and to go back to some earlier reading-writing life in which I had more honest concerns. But I couldn’t deny a whiff of self-sabotage here.

Amid these pushes and pulls of my mind, the decluttering insight came from the oddest, most unexpected source: me. One evening, I remembered the advice that I’d given another writer earlier in the day. It had seemed very intelligent when I’d said it, but it was absolutely piercing in a rerun. Writing well comes down to overcoming doubt and staying humble, I’d said. This, in turn, depends on deeply internalising two difficult truths, I’d added. The truths I’d mentioned were:

I am not small.

The world is bigger than me.

Sitting on the couch that evening, I realised that I’d deeply internalised the first truth. I had published four books, I had been mentioned in an award or two, my books had been written about, et cetera. I had reached a point where I knew I was at least an okay writer. I had reached a point where I was sure of publication in India. Anything that signified my smallness—a snub from a literary festival, say, or the opinion of a contrarian reviewer, or the brutality of royalty statements—I regarded as anomalous or temporary. This was a self-narrative, yes, but to conflate it with plain hubris or self-absorption would be wrong. I’d arrived at this point. It had taken me time. There was the flavour of achievement in it.

But the second truth, a truth that must have reigned over the ‘earlier reading-writing life’ that I now wanted to return to, had been “disinternalised”. I knew it, I believed it, and yet it was not concentric with me. I was convinced I needed to internalise this truth again. I needed to become a part of something that was incontrovertibly, and permanently, bigger than my ambition or chicanery, something that lay beyond the prismatic schemas inherent in the play of person, persona, and personality. Simply speaking, I needed something with the flavour of worship in it.

#

As the year neared its end, I observed that the books I had tended to pick up lately were getting smaller on average, as if a certain aversion to girth had been surreptitiously coded into me. There were Ernauxs, Modianos, Jim Thompsons, Amit Chaudhuris. This brought to memory the ‘bookish pharmacist’ who appears briefly in the second part of Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, translated from Spanish by Natasha Wimmer; the bookish pharmacist who ‘chose The Metamorphosis over The Trial, […] chose Bartleby over Moby Dick, […] chose A Simple Heart over Bouvard and Pecouchet, and A Christmas Carol over A Tale of Two Cities or The Pickwick Papers’; the bookish pharmacist who was, per the character named Amalfitano, ‘afraid to take on the great, imperfect, torrential works, books that blaze a path into the unknown.’

To read a great, imperfect, torrential work in 2024 became my immediate desire. But I didn’t want to read something like 2666, which is to say that I didn’t want a post-modern aggregation, fragments collected to resemble a loose baggy monster. I wanted the ‘real’ thing. I wanted to be guided in and through a LARGE story, one with a promise of comprehensiveness that would resist, if it needed resisting, a conception of realism as a serialisation of disparate elements. Perhaps I wanted to be in another ‘earlier time’, when Literature did what it did with moral ambition, with no sense of defeat, or at least not an overpowering sense of it, and with no weakness for the trappings of intense and self-reflexive irony.

It is sheer luck that I discovered Simon Haisell’s Substack readalong for Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace at around the same time. Participating in it is the best thing that has happened to me this year. The readalong’s communal aspect gave me a way to deploy a kind of bonhomous discipline to keep private pragmatism—and the relentless pull of the current—at bay. And what to say of War and Peace, perhaps the best example ever of what I was seeking. There isn’t a grander novel, in every sense of the word. No surprise that I saw the possibility of worship in it.

This radical, and positive, alteration in my reading also fed that other renegade impulse—that of wanting to take up abstruse writing projects. Caring little for whether or not there would be an audience for them, I started writing essays about my reading of War and Peace on Substack. But the third renegade impulse, to vanish from Instagram and Twitter, could not be serviced. Over January and February and March, as my engagement with the novel deepened day after day, the imperative of memorialising my awesomeness returned, that too in a fresh way, such that I now wanted every one of my followers to know the enriching project I was participating in and to appreciate the writing that I was producing around it.

I made carousel posts with snippets from my War and Peace essays. My Instagram stories started referring to the Napoleonic wars, or early-19th-century European dances, or serfdom in Tsarist Russia. And I talked about these things like I was talking about cool ‘in things’—in my mind the wars were of great import to everyone, appreciating the difference between an ecosaisse and a Russian folk dance was crucial, and tut-tutting about the state of the serfs was the least one could do. My reading of War and Peace and the abstruse writing projects emerging from it thus gave way to a public display of the abstruse and the concomitant cultivation of a persona around it. My affliction was complete.

I was unable to prevent a commingling of an authentic human experience with a perpetual clout-chasing project, leading to a situation that harmed both the authenticity of the experience and the objectives of the project. I was inside a joyful fugue of learning and imagining and hypothesising and theorising, and there was no need, none at all, to squeeze social media content out of it. Had my interests been more inclined towards the popular and my attention drawn more easily to whatever had the potential for virality, I would have picked some other social media game. I would not have posted about how seeing characters dance in Tolstoy’s novel made me note the absence of dancing in the contemporary novel, or how Tolstoy’s ease with mentioning down-to-the-last-ruble details of a character’s wealth made me think of how contemporary writers preferred being mum about their characters’ bank balances, or how Ridley Scott’s Napoleon resembled Tolstoy’s in pique and pettiness, or how the word ‘fichu’ had reminded me of Humbert Humbert ogling Dolores’ ‘shirred bra’.

Perhaps I was too much of a genuine article, so generous and playful with my attention to the novel, and so lively with tracking the micro-narratives this attention engendered, that I just assumed that I would get some attention in return. I should have known that the genuine finds no purchase on social media. My War and Peace posting stalled my Instagram growth, and any momentum I’d picked up through Manjhi’s Mayhem reels and reviews of slimmer books sputtered and extinguished. My professor would have been mightily displeased with whatever I was doing. I carried on, however, both with the delightful readalong and the compulsive sharing. I knew no better.

Then, one day, the book gave me a memorable scene which later became, under the stress of my considered attention, a metaphor—and a moniker—for my affliction.

#

Though there is much that happens during peacetime in War and Peace—multiple coming-of-age stories along with multiple complications around who marries whom and multiple approaches to the question of just what it is to be a human being—its wars provide not just its scaffolding but also its clearest windows into Tolstoy’s big subject: History. Tolstoy is generally suspicious of how History is written, and leans towards seeing History as a continuity with no remarkable agents and events, a mega human drama with countless microcosms. The bulk of the novel is set between France’s war with Russia and Austria in 1805, culminating in a Russo-Austrian defeat at the Battle of Austerlitz, and Napoleon’s Grande Armée’s invasion of Russia in 1812. Tolstoy enlivens all battles in the novel with small events, small events which can be funny or spiritual or ironic or ghastly, and as denotative of the randomness of war as they are of the possibility of a full spectrum of drama inside that cloud of violence. Generals doze off during military council meetings, soldiers casually mull raping nuns, officers freeze up at the idea of killing an enemy.

The 1812 French invasion of Russia is understood to have (symbolically) commenced with Napoleon and his army crossing the Niemen river. There are many paintings, none of them very good, marking the event as an event. In War and Peace, true to his penchant for challenging known History (and its mythologising lapses), Tolstoy dispenses with the Niemen crossing in just a couple of sentences, instead giving us our first episode from the invasion at the crossing of the next river, ‘the broad Viliya’. There, Napoleon stops near a regiment of Polish Uhlans (an uhlan is a cavalryman with a lance). Through an aide-de-camp he communicates to the regiment his order to find a ford and cross the river. But there is just too much excitement owing to his presence. Text from the Maude & Maude translation:

The colonel of Polish Uhlans, a handsome old man, flushed, and fumbling in his speech from excitement asked the aide-de-camp whether he would be permitted to swim the river with his Uhlans instead of seeking a ford. In evident fear of refusal, like a boy asking for permission to get on a horse, he begged to be allowed to swim across the river before the Emperor’s eyes. The aide-de-camp replied that probably the Emperor would not be displeased at this excess of zeal.

What follows is downright horrific. The colonel plunges into the water with his horse, towards the deepest part of the river, and hundreds of uhlans follow him. Forty of them drown to their deaths. Napoleon barely notices.

It was cold and uncanny in the rapid current in the middle of the stream, and the Uhlans caught hold of one another as they fell off their horses. Some of the horses were drowned and some of the men, the others tried to swim on, some in the saddle and some clinging to their horses’ manes. They tried to make their way forward to the opposite bank, and though there was a ford half a verst away, were proud that they were swimming and drowning in this river under the eyes of the man who sat on the log and was not even looking at what they were doing. When the aide-de-camp having returned and choosing an opportune moment ventured to draw the Emperor’s attention to the devotion of the Poles to his person, the little man in the grey overcoat got up and having summoned Berthier began pacing up and down the bank with him, giving him instructions and occasionally glancing disapprovingly at the drowning Uhlans who distracted his attention.

That evening, between two other orders, Napoleon gives instructions ‘that the Polish colonel who had needlessly plunged into the river should be enrolled in the Légion d’honneur of which Napoleon was himself the head.’

When I read this episode the first time, the cinematic pageant of needless death and the aleatory bestowing of honour that followed it struck me as astonishing and memorable. I saw the commotion in the water, the splashing and thrashing and the shrieking; and I saw Napoleon’s vexation at both the sight and its memory. The episode also offered an opportunity, it seemed to me, to be turned into a metaphor. But precisely what it could be a metaphor for remained unclear. I wondered what explained, in today’s terms, what the uhlans had done? Were their actions committed out of love or rapture, or were their actions a martial form of celebrity-pandering, their risk perceptions all thrown out of the window at the sight of a person understood to be supreme in some way? To exist in the mind of Napoleon for just a moment seems to be worth more to the uhlans than existence itself. But what use are they dead to Napoleon? The war hasn’t even begun.

With these arguments, it might be tempting to call the uhlans stupid, but this take would be simplistic and off the mark. There is most certainly an element of strategic clout-chasing in the uhlans’ actions. They are careerists willing to risk death, perhaps because for a lancer, death is anyway never too far away. And whether it comes on the Russian steppes or under the surface of the Viliya, it is always better if it is preceded by some visible derring-do. One could call it a commitment to performing unto death, and insofar as death comes without a warning, such a commitment requires being ever alert to opportunities for such performance. To the uhlans, death is de rigueur; the bigger risk is that of being unseen.

When I regard the uhlans this way, a patchy metaphor begins to form itself: Writers are Polish uhlans, committed to crossing the Viliya of social media (or offline performance) every day on their horses of good work, hoping desperately to be noticed by their Napoleon, the inscrutable algorithm that bestows any and all validation and offers to a selected few an improved station in life. The biggest risk for writers is being unseen. Their careerism must manifest in explicit performance, and they must be ever alert to the possibility of one. And, yes, they have to commit to these processes until death.

#

I have written this essay from Muzaffarnagar, my hometown. I came here about a week ago, with the idea of spending a few days with my mother. In this time, there have been some experiences so far removed from what is usual for me nowadays that they appear to belong to an earlier life: guavas plucked from the tree right next to our gate; two meals of lauki from a farm not too far from where we live; long matches of plastic-ball cricket with my cousin, who is twenty-three years my junior and lives with my mother; and relentless gossiping, for its own joy, about those who matter little.

These experiences are surplus to a great benefit: crucial progress made in my work-in-progress novel. Chasing this progress was at least partly my objective for this trip. I was in a writing lull—crossing the Viliya every day, so to speak, but out of tune with the larger picture and paralysed because of a disjunction with both authentic engagements and my persona-building. Muzaffarnagar offered sanctuary. Here, the word ‘performance’ has a completely different connotation for me, similar to what it means for sportspersons, with aspects of ‘effort’ and ‘play’. This is where I studied hard through school, then for competitive exams, and then during vacations from college. This is where I read my first stories in English, expanded my vocabulary, practiced composition. This is where I lived a life far from the Viliya, always in tune with the bigger picture of the day (which, incidentally, was the necessity of escaping Muzaffarnagar and reaching a bigger city). This is where I have a history of hunkering down and grinding it out and coming out of it better off.

Over the last few days, I have written thousands of words. I have read many chapters of War and Peace. And I have posted next to nothing on Instagram or Twitter. This last act is no definitive reversal. I’ll be crossing the Viliya again. And I’ll have fun doing it. I embrace my station, and the supremacy and unknowability of my Napoleon, for in this small town, I’ve centred the truth I needed to centre. The world is bigger than me. The world is bigger than me every day. The world is bigger than me every day for its own reasons, but also because it makes me cross the Viliya every day. I am not small, however. I am not small because I have given a name to this thing that I have to do every day. And I plucked this name from the middle of a big book, which I was free to come to and draw a metaphor from. The world is bigger than me because it places injunctions on me; and I am not small because I am free to enjoy them.

——

TANUJ SOLANKI is the author of four books of fiction, including the short-story collection Diwali in Muzaffarnagar, which won the Sahitya Akademi Yuva Puraskar in 2019. For more of his work, see his personal substack which has “reviews, essays, notes on reading, notes on writing, and sometimes a short story”.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Banner: Copyright holder unknown.

We hope you enjoyed reading this issue of Crow & Colophon. Subscribe for free to receive updates about The Bombay Literary Magazine and notes of a literary persuasion.

Tanuj, I read this piece and was simply blown away - the scope, the size, the discipline and the overall 'message' to use an ugly word. I struggle to tell people what this is about, because any definition seems to reduce it. It is vast, it contains multitudes. Kind of like War and Peace! Terrific