The publishing date for the second issue (#58) of The Bombay Literary Magazine is just two weeks away (August 15), and the Crow’s minions are busy, busy, busy. It’s a good kind of busy though, and knowing that the urgency is entirely self-imposed just makes it better. There’s great satisfaction in pointless usefulness.

It’s hard to say if the universe is constructed on the same general principle. Unfortunately, the problem seems to require logarithms and tangents and what not, and we humans are pretty much lost after compound fractions. But it’s safe to guess that the black disk of the cosmos isn’t spinning around at 33.33333 revolutions per minute, with God’s infinitely compassionate needle transmuting the grooves and cuts of our lives into song. Or maybe it is.

In this post, Sanjay Chaube talks about an Urdu poet, “Ghalib”, who seems to have felt the touch of the needle a tad more keenly than most.

Colophon: God, Ghalib and I

SANJAY CHAUBE

I was born in Lucknow, a city which had been crumbling for about a hundred years before I was born. It is about two hundred and fifty dusty miles from Delhi, where the dying flame of Mughal culture sputtered and burned out soon after the British ruthlessly put down the Great Rebellion of 1857. But the lamp burned brightest before it went out, as the cliche goes. The name of that flame was Ghalib.

I grew up with the poetry of Ghalib in Lucknow. He was like Shakespeare—everyone around me had heard of him, many quoted him, most didn’t understand him except for the popular quotes, and it was generally understood that you could have no literary pretensions if you didn’t know him. He wrote his poetry in Urdu, that beautiful mongrel tongue, a happy mixture of Hindi, Persian and Arabic. It was a language, my father said, which could express thoughts that could not be expressed in any other language. (Well, actually he said “Urdu and French”. I don’t know much French poetry, except Baudelaire.)

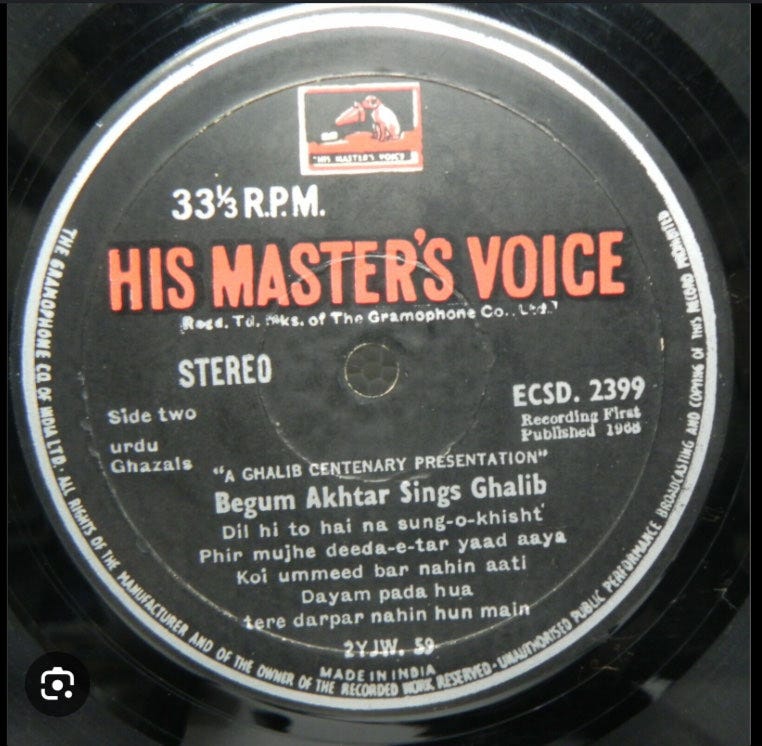

I heard Urdu poetry recited and sung and quoted, by my uncles and aunts and my grandfather, and by visitors to our family mansion. Most wondrously, I heard it on vinyl records, sung by Begum Akhtar. Her voice was like no other in India, before or since. It was certainly very different from the voices I heard in Hindi films, which in those days were pretty much limited to the Mangeshkar sisters. For one, Begum Akhtar’s voice couldn’t be classified as manly or womanly, although it was manifestly a woman singing. It had a conversational quality to it. Leisurely. Casual. It was throaty and nasally and mellifluous and guttural by turns. I had a suspicion she smoked hookah like a fiend. She had a style. She would sing one line lazily, behind the beat of the tabla by a good bit, then the last notes would fritter away in the air like startled birds, she would pause, and then sing the next phrase with the authority and weight of a Mughal emperor. And then there were those unexpected moments when, in the middle of a line, she seemed to be trying to swallow a small frog. My grandfather described it as a “khatka”, a word akin to “glitch”. As if she had been singing while sitting in an Ambassador car which had just hit a pothole. Her singing had the supernatural quality of making me want to cry and pray at the same time. She was the Etta James of my childhood. And she sang Ghalib.

Five years ago my friend Aman recited a ghazal by Ghalib, in its entirety. At the risk of informing the already well-informed, a ghazal is a poem in couplets, each couplet is called a sher (plural: ashar), and the rhyme goes a-a, b-a, c-a, d-a, etc. A ghazal is either recited or sung, at gatherings called mushairas. The convention is that the poet gives you the first line of the sher, the setup, and then waits for the tension to build, often repeating the first line to build up suspense. And then comes the second line, which resolves the question, the tension.

If the sher is really good you don’t have the resolution until the last words of the second line are spoken. By convention, the last sher of a ghazal, called the maqta, includes the name of the poet. It’s like signing a piece of art, so everyone who reads it out loud knows who composed it. “Ghalib” (“Victorious”) is a nom de plume. He also used his given name, “Asad” (“Lion”) in the maqta of some ghazals.

I grew up thinking a ghazal was built around some unifying theme, usually the longing for a lost love, but as Aman recited this ghazal I realized that this did not have to be the case. In this ghazal each sher was atomic, a tiny universe in two lines. I was familiar with this particular ghazal (“Yeh na thi hamari kismat”), because I grew up listening to Begum Akhtar singing it. One sher is full of strange nihilistic longing:

Hue mar ke hum jo rusva hue kyon na garke dariya?

Na kahin janaza uthta, na kahin mazaar hota.If I had to die in disgrace why couldn’t I have just drowned?

No pallbearers, no mausoleum.

No fuss, in other words.

As Aman recited the ghazal, I realized I didn’t know Ghalib half as well as I thought I did. Two weeks later, I bought a copy of his Diwan (“Collection”) at the airport in New Delhi. The first sher of the first ghazal induced vertigo and confusion:

Naqsh fariyadi hai kiski shokhi-e-tehrir ka

Kagazi hai pairahan har paikar-e-tasvir ka

Whose mischievous brush strokes is the picture complaining about?

Every character in this painting is wearing paper clothes.

Wait, what? The rest of the ashar in the ghazal were equally opaque. I turned to the next ghazal. Same deal. I gave up. For the next two years the Diwan gathered dust on a bookshelf, silently reproaching me for my laziness. When I picked it up again and had another go I knew that I couldn’t do it casually. I started studying Ghalib seriously, systematically. It was heavy going, like Shakespeare is heavy going until you learn to swim in Elizabethan English. I realized that I needed a really good Urdu dictionary. I found it on Rekhta.org. It was really good, not least because it gives etymologies.

I soon gave up on my copy of the Diwan, and switched to reading it on the Columbia University website, developed by Frances Pritchett, who is the greatest thing to happen to Ghalib scholarship in a long while. I went back to the very first sher of the very first ghazal, and over the next two weeks I discovered that several things are happening here.

There is the obvious metaphor of the-world-as-picture, but with the (postmodern) twist that the characters in the picture are alive, and complaining about the painter. But wait! It’s useless to petition God, says Ghalib, because either your maker is wilfully capricious (in which case just accept this mess as Allah’s will), or playfully mischievous (and you can join in with Him and chuckle along ruefully). Now, the second line. In Ghalib’s day all pictures were painted on paper. So, in an obvious sense, every character in the picture had clothes made of paper. (But paper captures so beautifully the ephemeral nature of human existence, yes?) After pondering this sher for a week and getting nowhere I gave up and turned to the commentaries, where I found that Ghalib mentions in a letter that people in Persia wore paper clothes when they went with a complaint to the Shah. But if everyone is wearing paper clothes, if everyone is a supplicant, then so is the Shah! So what’s the point of wailing and gnashing your teeth in his presence? Since I have a suspicious imagination, I then pictured God in his cosmic studio, complaining about the poor quality of His material: ”Dammit, why did I have to paint these creatures with paper clothes? Now all they do is piss and moan! Oh damn, now they’ve got me complaining! Aargh!”

Now the question posed in the first line becomes doubly rhetorical. If God is capricious/mischievous, and may also be a plaintiff, then what profits a man to complain? In any case, this is what He made, so shut up and deal with it.

(There’s a final joke in all this. Several scholars of Persian history have said that they know of no such tradition in Persia. The custom of wearing paper clothes seems to be a complete (and mischievous?) invention by Ghalib. Well, fuck!, is all I can say.)

So here’s the poet, in the opening lines of the Diwan, gazing upon humans and telling them their complaints to God are bootless. That first sher took me two weeks to understand. The entire first ghazal took me six weeks. Ghalib called himself mushqil-pasand (“obscure by choice”) with good reason.

Apparently, I wasn’t the first one flummoxed by this ghazal. In Gulzar’s television retelling of the story the literati in Zafar’s court are equally clueless when Ghalib first recites it. And they knew far more Urdu than I ever would. Over the next two and a half years I went through all 234 ghazals of his Diwan. Some are funny as fuck. . Some are grotesque. Some chilled me to my marrow with existential dread. There are quite a few in praise of booze (which Ghalib was so fond of that he often found himself in trouble for unpaid bills at the local liquor store). Not all his ashar are glittering gems of literature. Some are too opaque, others are only mildly interesting. I’ll let you figure that out for yourselves when you read his Diwan. I want to talk about a running theme in the Diwan which fascinated the religious skeptic in me.

After having read a few dozen of the ghazals I realized that Ghalib is stubbornly unreligious. Which is not to say he is a kaafir, an unbeliever, but rather a persistent questioner of the orthodoxy of his day. He says so himself, in one of the eulogies he wrote for himself:

Hui muddat ki Ghalib mar gaya par yaad aata hai

Vo har ik baat par kehna ki yoon hota toh kya hota

It’s been ages since Ghalib died, but we remember

That he said, at every turn, “How would things have been had they been otherwise?”

In one of his most famous and oft quoted ashar, he wrote:

Na tha kucch toh khuda tha, kucch na hota toh khuda hota

Duboya mujh ko hone ne, na hota main toh kya hotaWhen there was nothing there was God, and if nothing existed God would have existed.

‘Existence’ ruined me. What would have been had I not existed?

The first line is a pretty bland setup, a common piety in many religious traditions. But how are we to tie this with the second line? That question Ghalib asks in the second line is commonly interpreted as rhetorical: ”What difference would it have made had I not existed?”

But the wonderful thing about Ghalib is that his ashar are multivalent, so a more head-scratching meaning is given by interpolating the first person singular: ”What would [I] have been had I not existed?”. Hmm, I don’t know, dude. Neither of those interpretations gives any clue about how the first line relates to the second. I suggest that a more piquant reading of the second line is: “Existence ruined me. Maybe all existence is ruinous. So maybe the existence of God is not such a good thing, either”.

That, of course, is heretical, and Ghalib was never openly heterodox, but his language is slippable enough to allow for such blasphemous readings. Another possible meaning of the entire sher could be: “Since God is perfectly capable of existence in an empty universe, what was the point in creating us, since existence is so ruinous?”

This slyness, made possible by the openness of his language, this persistent questioning of the established order of existence, this independence of thought is why I love Ghalib. There are places where he apologises for his freethinking, but even when he is contrite he isn’t, not really. He sounds like someone saying: “Yeah yeah, I’m a sinner, but I don’t have it in me to reform”. Here’s another one of Ghalib’s self-euolgies:

Ye laash-e be-kafan Asad-e khasta-jaan ki hai

Haq magfirat kare ajab azaad mard thaThis naked corpse belongs to Asad the Broken Hearted

May God forgive him, he was a strangely independent fellow.

In one ghazal (“Koi ummid bar nahin aati”) he wrote:

Jaanta huun savab-e-ta’at-o-zohad

Par tabiyat idhar nahin aatiI know, I know the obedient and devout are blessed,

But lately here I just don’t feel like it.

In the last sher of the same ghazal, he scolds himself gently in the second person:

Kaaba kis muh se jaoge Ghalib

Sharm tumko magar nahin aati.Ghalib, how are you going to show your face at the Kaaba?

But you don’t really feel shame, do you?

I suspect these expressions of half-hearted guilt were actually a cover for underlying hubris. Here’s a sher in which he shows the stiff spine of the egotist in the presence of God. (Notice his use of the royal “we”):

Bandagi mein bhi vo azada-o-khud-been hain ki hum

Ulte phir aaye dar-e-kaaba agar va na hua.Even in submission we are so free and conceited that we

Would turn around and go home if the door to the Kaaba were closed

The sheer chutzpah is staggering. Yeah, I traveled a month, I crossed an ocean to get to Mecca, but seriously, who’s got the time to stand around and wait for the doors to open! This sher made perfect sense when I read an anecdote about the time the British offered him a job teaching Persian at the Delhi College. Ghalib, who lived in genteel poverty all his life, went to the job interview in a palanquin, parked outside, and waited for the secretary, a Mr. Thomason, to come out and welcome him in. It was something Ghalib thought was his due, him being an aristocrat and all. Well, the Englishman was either unaware of the niceties of Delhi culture, or he just didn’t give a fuck, so after waiting for a few minutes Ghalib told the palanquin bearers to take him home. Yeah.

Speaking of the Kaaba, you probably know that every mosque around the world has a niche, called a mihrab, which is always built in the direction of Mecca, and the mosque in Mecca also has a niche, called the qibla, which points to the Kaaba, the monolith at the center of the Muslim world. (This architectural necessity is one reason why the Arabs became very, very good at making compasses—it was a matter of afterlife and death.) But of course Ghalib is impatient with all these material trappings of religion, an attitude which is very Sufi —ultimate reality is not of this world, real truth cannot be apprehended with human senses, everything is meta-something, all that sort of thing. How much of this is just plain old snobbery is anyone’s guess, but Ghalib takes it to the next level in this sher:

Hai parey sarhad-e idraak se apna masjood

Qible ko ahl-e-nazar qibla-numa kehte hain.

What I bow down to is beyond the limits of perception.

The qibla is called the qibla-compass by people of vision.

What is being said here? The qibla is the compass that points toward the Kaaba, so calling the qibla “the compass that points toward the qibla” is pretty self-referential, to say the least. Why would a compass point to itself? What would be the point? But it gets worse. If the qibla is no longer pointing to the Kaaba, but to itself, how does the pointing happen in the first place? How can you use your index finger to point to itself? You see the difficulties? It’s a bit like saying “This sentence is talking about itself”, a perfectly legitimate grammatical construction, but a perfectly useless sentence, no? Have you seen MC Escher’s lithograph “Drawing Hands”, where the right hand is holding a pencil, drawing the left hand, and the left hand is holding a pencil, drawing the right hand? If you ‘get’ that picture, you get the picture. This is the zen of Ghalib.

This sher reminded me of the movie Enter The Dragon, which I adored as a teenager. Remember the sequence near the beginning, where Bruce Lee is training a slack-jawed teenager to fight? At one point he says “It’s like a finger pointing away to the moon”, and when the boy stares at Bruce Lee’s finger he gets whacked upside the head: “Don’t concentrate on the finger or you will miss all that heavenly glory!” Yeah!

But Ghalib’s impatience with the pieties of religion is tempered by the realization that people need illusions to live by. When speaking of the promises of paradise in the afterlife, he is drily sarcastic, but there is a “but”. (Notice the royal “we” again):

Hum ko maaloom hai jannat ki haqiqat lekin

Dil ke khush rakhne ko Ghalib ye khayal acchha haiWe know the truth behind the whole “paradise” thing. But

It’s a nice thought, it keeps the heart happy, Ghalib.

So that’s a bit of Ghalib, the eternal questioner, the riddler, the half-repentant sinner, one of the greatest poets to ever get drunk. I’ll leave you with this one last sher, which happens to be the last sher, the maqta, of the ghazal I quoted from at the beginning of this piece, a sher in which he undercuts everything he’s said before:

Yeh masail-e-tasavvuf yeh tera bayaan Ghalib

Tujhe hum vali samajhte jo na bada-khvar hotaAll these Sufi exegeses, all this deep stuff you say, Ghalib,

We would have thought you the Enlightened One, had you not been a drunk.

Note: All translations are mine.

——

SANJAY CHAUBE was fortunate enough to be born in Lucknow. He thinks Guide is the greatest Hindi film of all time. He plays bass guitar in a jazz band in New Orleans. He practices and teaches medicine because he has bills to pay.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Banner: Copyright holder unknown.

We hope you enjoyed reading this issue of Crow & Colophon. Subscribe for free to receive updates about The Bombay Literary Magazine and notes of a literary persuasion.

This is wonderful. Thank you so much. Isn't skepticism another kind of faith and irony a kind of religious practice?