Every Force Evolves A Form

Amitabha Bagchi on the writing of a novel

First, an update from the Department of Weights & Measures: if you’d submitted an item to be weighed for TBLM’s Issue 59 (December 2024), then we’ll send you an update by the end of November. If you still haven’t heard from us by then, drop a line to help@bombaylitmag.com. But please check your spam/promotions folder first.

We also have some happy news: Ajay Kumar Nair, whose poems we’d published in 2021, has just been awarded the Srinivas Rayaprol Poetry Prize 2024. Congratulations, Ajay.

The two poems we published, touchscream and homecome are in the form of unrhymed open couplets. We refer to things like couplets as poetic forms, but perhaps they are better understood as forces shaping the author’s intent into specific expressions. Indeed, why just poetry? Why not art itself? The Shakers took it on faith that every force evolves a form. “A work of art,” claimed the critic Guy Davenport, “is a form that articulates forces, making them intelligible”. In Ajay’s poems, it’s possible to detect the presence of such forces. The images wind their way through the fragments, slide past the enjambments, leap over the line spaces, and eventually perch, tentatively, in a meditative silence: a meaning, if you will. Here’s the opening of homecome:

by morning, we arrive & the first thing I see

is the hand pipe planted in the front yard witha hose running all the way to the toilet in the

back fitted with a new western / grandpa gets…

and it comes to a rest on a tercet:

…

of sawdust walking through a dam of coconut shells to unbury

a VHS & some pills & a corpse of a fat lizard / by next morning

we depart, waving hands to erase some inevitable unseen shape

Grandpa ain’t gonna live for long. We wave our hands, record our understanding of the departure. These poems feel as if they were meant to be written by hand, just as God intended, iron gall on paper, rather than forcing one’s digits to tap-dance like sozzled Irishmen on a keyboard.

We are both progenitor and progeny of our tools. What we write with exerts a force on us. And something evolves. One of the threads in Amitabha Bagchi’s essay is how a change in tools coincided with the writing of a novel he wasn’t entirely aware he was writing. But our promises speed ahead of the text. Over to Amitabha.

Colophon: A Cursive Discontinuity

Somewhere near the end of 2003, a few months before I completed the first draft of my first novel Above Average, someone who didn’t know me well but had been told I was a writer–a new girlfriend’s mother–gave me a present I didn’t know what to do with: a notebook. I had been writing fiction regularly for seven years at the time but I can’t recall having handwritten a single word of it. In college in Delhi before 1996 I would sometimes enter creative writing competitions and there, of course, handwriting was the norm in the sense that in Delhi in the mid-nineties no one had yet imagined the future, not so far away at the time, where all meaningful writing was going to be done on a laptop. But in 1996 I had moved to the US for graduate school and had been given a desk with a computer sitting on it with internet access and all that. The upshot of this, in those lonely early days in a new country far from home, was that I spent much of my time writing emails to my friends from college–who had also moved on to graduate studies in India or overseas and, thereby, acquired access to email too.

After months of writing long, painstakingly paginated emails, when I tried my hand at a short story I found that this regular exercise had somehow helped me acquire some amount of writing stamina. In college writing competitions I would struggle to scratch out eight hundred or a thousand words with a ballpoint pen and that too only because of the exam room atmosphere the organisers provided for this purpose, and the one-hour time limit. At the end of it I would be exhausted. Now I found that a thousand words felt like a good beginning, something I could sit down with over a long evening at my desk after dinner, moving up and down the editor window, shuffling, deleting, rewriting at will.

Like many other people in those transitional days I too found the flexibility of writing on a computer seductive, but what had drawn me to writing fiction that way was not my need to finesse my work even while composing the first draft. What had drawn me to the computer was that it connected me back to my friends, that I was lonely, that I wanted to communicate something of what I was feeling to people who I thought might care, that phone calls to India were prohibitively expensive. These circumstances had come together to develop my writing muscle where by writing muscle I mean the basic ability to spend time thinking through what it is you want to say and then composing and typing out the sentences and paragraphs that were intended to capture those thoughts. This writing muscle came into play, and, I was pleased to learn, grew even if those thoughts involved less than exalted material like complaints about how stingy your roommate was on top of being a pure vegetarian, or how confusingly varied the offerings at a US university cafeteria’s salad counter were. It came as a pleasant surprise to me that the time and effort I had spent on this kind of writing–writing that I considered unimportant but did nonetheless–had helped me when it came to the kind of writing that I thought was more important: the fiction writing that I thought would make a famous writer out of me.

All the fiction I wrote was carefully organised in files and directories on my department’s filesystem. (The nomenclature itself reveals how the mode that had seemed tech-savvy and current at the time was to sound hopelessly dated within a couple of decades: many seventeen-year-olds today don’t know what a file is and no one except Unix nerds would call a folder a directory now.) All the handwriting I did at that time was my own name and address on the self-addressed stamped envelopes I sent to various journals and magazines along with my short stories, and that handwriting quickly developed a negative connotation because almost all those stories were rejected and the sight of my own handwriting in my mailbox–a physical one–was the cue that initiated the spiral of disappointment and hopelessness that each rejection brought.

When I finished the first draft of Above Average in 2004 and started sending query letters out to agents, those self-addressed envelopes seamlessly made the transition to informing me that the bigger disappointment of having an entire novel rejected lay within. I guess it isn’t surprising then that writing by hand didn’t appeal to me much in those days. Not even when I discovered, around a decade ago, that the files containing my early short stories had been corrupted somewhere in the transition from Unix to Windows to MacOS, and were unrecoverable, did I say to myself, “If I had handwritten these I would still have them, ballpoint ink doesn’t even fade!”

In the age of social media everyone knows that entrenched points of view get even more entrenched when faced with opposing points of view and so it was with me. When a famous writer talked about how he only writes by hand and that too only on paper that is at least 100 GSM–almost artwork quality–I dismissed it as an affectation, especially since his claim lay at the intersection of two of my established dislikes: one to do with handwriting and the other to do with writers talking about the physical aspects of their writing– “Unless I am looking out at the vine-clad brick wall of my beautiful house in a quiet and tree-lined enclave that ninety-nine percent of the population can’t afford to even dream of, I am not able to compose my cris de couer in support of the underprivileged!” Long story short, I got through a couple of decades with my laptop as my primary, in fact only, writing instrument, carefully organising my directories–saying “folders” feels like the linguistic equivalent of colouring my hair to appear younger than I am–and making the kind of backups required to ensure the persistence of (silicon-based) memory. But Muneer Niazi has said,

“Hamesha ek hi aalam mein hona ho nahin sakta

musalsal ka kahin aa kar badalna bhi zaroori tha”

(things cannot go on for ever in the very same way

a break in continuity, that was needed too),

and, like many other continuities, mine too broke in the last decade that began with Modi 2014, continued into Trump 2016, Brexit, reached a cataclysmic high note with the pandemic and, just when it felt like it couldn’t get worse, ended in the continuing calamity of Gaza.

None of these world events affected me directly, of course, although, like everyone else, I like to think that history’s large movements are, in fact, no more than plot points in the unendingly fascinating story of my life. What happened to me just before this decade began was something a little more prosaic, something that happens to everyone and used to happen even when this disastrous decade was millennia in the future: my father died. In the long and tortuous journey of grief that this event inaugurated, I found my way to writing a novel in which everything I had read and everything I had felt in the two decades or so prior to that moment of loss came pouring out, every version of every half-developed idea for a character or a situation, and I had to struggle to manage it all because every thought I had about that book felt like a twist to the dagger that was lodged in my heart in those days. It isn’t particularly relevant for this piece to recount it in more detail than that, suffice it say that in June 2017 when I typed in the last word of the first draft of that book–it appeared in 2018 under the title Half the Night Is Gone–I was the emotional equivalent of the marathon runner who collapses right after finishing, dehydrated and a few kilograms lighter than when he began.

In the four years or so that I had been in the thrall of this book–or battling my grief, whichever way you want to look at it–I had continued doing my job and being a husband to my wife, son to my mother and father to my son, but, nonetheless, when the first draft of Half the Night Is Gone ended I found myself waking up to a world that didn’t much resemble the one I had left behind when I entered that dark tunnel. My son had turned seven and while still a child was no longer a baby. Many new people had joined my department and I was now a “senior colleague” to more people than I was “junior colleague” to. A particular brand of hateful and parochial thinking had become normalised in our country. Trump, who I had known from my time in the US as a buffoon, was now President. And so on. Muneer Niazi has said,

“Gali ke baahar sare manzar badal chuke the

jab saya-e-koo-e-yaar utara, to meine dekha”

(outside that lane everything the eye could see had changed

when the shadows lifted from my lover’s street then I saw)

and that felt truer to me in 2017-18 than it ever had before. I felt disoriented, adrift, and responded to this sensation in the only way I could think of: I tried to write a new novel.

In retrospect it appears obvious that the attempt to write a new novel in the aftermath of the emotional churn I had been through was bound to fail—not for all writers perhaps, perhaps just for me—but at that time I went through the motions with utmost seriousness. At first there was, of course, the idea of writing a sequel to Half the Night Is Gone, or rather the second book in what I had rather grandiosely thought of as a trilogy covering the twentieth century. I made the required directories on my laptop and began making notes in google docs (a new modality that had crossed the river that separated my day job from my writing at some point when I wasn’t looking.) That went nowhere fast, or, rather, that went nowhere slowly since it took me two years to realise that it simply was not going to happen and that I needed to let it go. The thought of writing a sequel to Above Average came and went in that period, dismissed because it felt like following that idea would be to admit that I had run out of ideas.

In early 2019 I turned to translating Muneer Niazi’s ghazals in the hope that the process would help me find a new voice and that a new novel would come along with the new voice. I think I found that voice but it turned out there was no novel included in the package. The pandemic came and, like every other writer, I started a lockdown journal on google docs, but one that was backward looking–the present had always been hard for me to make sense of as it was happening and this particular version of the present, Delta wave and what not, was not even the garden variety present that I had been faced with earlier. There was time to write, plenty of it, but there was a stunned silence within, so I spent time making notes about some things that had happened years earlier when I first went to the US in 1996.

Eventually, by mid 2022 I had some new ideas, a new character, a voice that was not new enough for my liking but could possibly pan out, and I began writing out notes in Google Docs and even filling out some text files with actual text. But by the time 2023 rolled around I had run dry. I didn’t feel like shutting the door on this one, but it wasn’t moving either. Almost six years had passed since I had written my last published book and finally I admitted to myself that I was flapping, trying too hard to do something that was not there to be done. The only sensible thing to do at this point was to give up, and so I made appropriate back ups of all the files that needed backing up, and then I gave up.

Some time after this I remembered that notebook I had been given in 2003. Although it is true that when I was given it I hadn’t known what to do with it, the fact is that I had used it. For a year in 2004-05 before moving back to India for good, in the aftermath of a breakup with the girl whose mother had given me that notebook, single and lonely, not able to see what life was to bring, I had used that notebook as a journal. Devoid of any ideas for what to write I had, nonetheless, scribbled long notes in it, notes that I remembered being frustrated at writing because they weren’t leading to anything. For a son of the urban Indian middle class everything has to lead to something, otherwise it is of no value. One half-remembered incident–sitting in a plane, tray table down with the notebook open on it and the person next to me asks “are you a writer?” and I don’t know what to say because at least twenty US agents and three Indian publishers have already rejected my novel, and a son of the urban Indian middle class can’t claim to be a writer unless he is a published writer.

Perhaps it was that I felt as unsure of myself in 2023 as I had felt that day on the plane in 2004, or perhaps it was because I remembered that when I wrote those entries in that notebook back then the goal had been just to write, just to compose sentences, because, like looking out onto the ocean or walking through a forest, composing sentences is a deeply soothing form of pleasure. But the analogy ends there because to compose sentences you need to have something to write about. And herein lay the problem that had dogged me for the six years that had passed since I wrote the last sentence of Half the Night Is Gone. Nothing had seemed worth writing about. But in March 2023 the urge to write got the better of me. By giving up on writing a novel I had unshackled that urge, and now it wanted its play. There were some old relationships from that past that had been bothering me, some things I had written down during the lockdown that felt incomplete, and there was this Moleskine notebook that belonged to my wife and had been lying around unused for so long that its elastic band had gone slack. I picked it up and slipped it into the backpack I carry to work and I began writing in it with a ballpoint, ten minutes some days, some days twenty, some days not at all.

As one day after another passed, I found myself in a situation I hadn’t been in before. I would start writing with some intention and would get sidetracked into something else. In the past I had never begun the actual writing without having a good idea of the import of the section I was to write, allowing the play of intuition to guide me in fleshing out my thoughts as I wrote, but not much more than that. But now that same intuition had freer rein and it led me in directions I hadn’t expected to go, it discovered for me things I hadn’t known were there within me waiting to be discovered. I realised now what the critic Supriya Nair had meant when she said that Half the Night Is Gone was a very “deliberate” work. When I first read her review, I hadn’t been sure if it was a criticism, but as I filled pages of the notebook that were only for me to read, as I let the pen run across the page line by line, I realised that it had indeed been a criticism, a valid one. She was indicating the absence of the lightness that comes with letting go, the sensation of a stone skipping across water.

Possibly the reader has figured out where this story is headed: a few months into the scribbling (still diminishing the act through verb choice!) I realised that there was a novel in all of this, a sequel to Above Average, but a very different one from the one I had thought of earlier and discarded. The voice had come when I stopped searching for it. Perhaps the voice had come because I stopped searching for it. And it had brought a novel with it this time. In the movie Forty Year-old Virgin, one of his friends tells the Steve Correll character that he wasn’t getting laid because he was “putting the pussy on a pedestal.” I hadn’t been able to write because I had been putting the prose on a pedestal. When I allowed it to come down off the pedestal, it gave itself to me willingly and I took it without making a big deal out of it because, writing, like sex, really isn’t as big a deal as everyone makes of it, unless you wilfully make a big deal out of it.

Now the writers who are just starting out are firing up their Amazon apps to order notebooks they can write in (the Amazon brand is cheaper than Moleskine and just as good, no I am not an “affiliate”) but there is a caveat here. I wrote that novel, soon to be published under the title Unknown City, over a couple of notebooks but when I tried the same stunt on the as yet untitled one I am working on now I ran into a wall, and I remain splattered against that wall as I write this piece. Now what? Voice to text? ChatGPT? Never! Never? Isn’t that what I had said about writing by hand? Some solution will have to be found. But first I need to type this piece into my laptop. That’s going to be a pain.

——

AMITABHA BAGCHI is the author of four novels and a volume of translations of the ghazals of Muneer Niazi, Lost Paradise. His fourth novel, Half the Night Is Gone won the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature in 2019. His fifth novel Unknown City is due in January 2025 and is a sequel to his bestselling debut Above Average.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

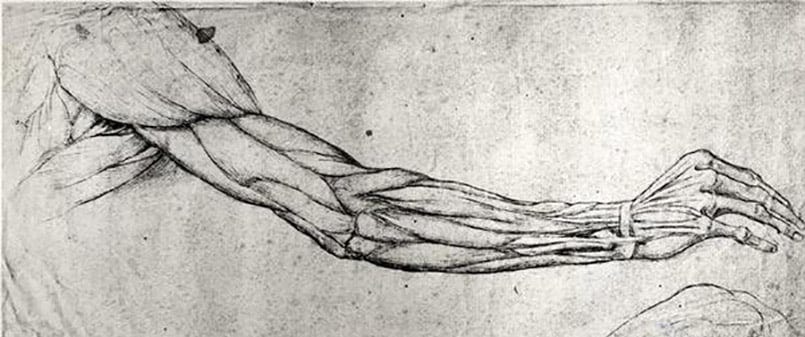

Banner image: Study of Arms. Leonarado da Vinci. Pen & ink on paper. Image, courtesy The Bridgeman Art Library.

We hope you enjoyed reading this issue of Crow & Colophon. Subscribe for free to receive updates about The Bombay Literary Magazine and notes of a literary persuasion.

Thank you for this article. There’s a mistake in the spelling of « I am not able to compose my cris de couer in support of the underprivileged!”

The correct way is « cri de cœur ».

Bravo to the author.